Indonesian Economic Outlook: Q1 (January-March) 2024

Business EnvironmentJakarta

sanomat.jak@gov.fi

Short-term overview: Robust growth with slight easing prospect

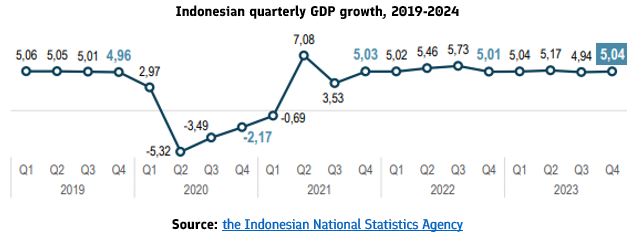

Indonesian economy enjoyed an unexpectedly smooth sailing in 2023. The country closed up with a 5.04% year-on-year GDP growth in Q4 2023. Indonesia continues to ramp-up stable economic growth since it bounced back from the pandemic crisis in 2021, with a 5.05% average growth in 2023, slightly slowing down from the 5.3% average in 2022. Global financial institutions such as the World Bank predicted that the economic growth will further ease slightly to about 4.9% during the next two years.

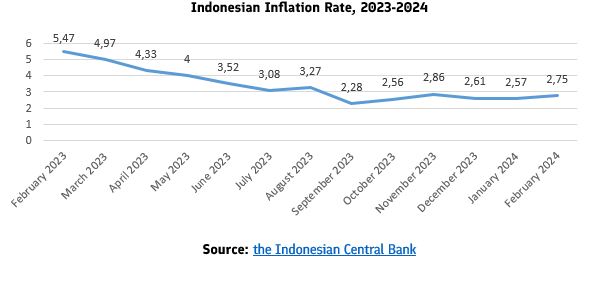

In the financial front, Indonesia can pride itself for successfully pushing down inflation for the last two years. The inflation rate as of February is at 2.75%, which is under the maximum ceiling rate of 3% set by the government. The main pillar of Indonesia’s tight grip on monetary policies is the Central Bank’s six-step increase of interest rate. It is rumoured that the institution, which is supposed to determine interest rate out of political intervention, will only start to make its first rate cut around mid-2024.

Medium-term overview: Shadows of fiscal imbalance

Currently, the government is preparing the draft for the 2025 state budget, which is set to be reviewed and approved by the Parliament on August. The current Ministry of Finance has committed to inheriting a healthy state budget composition that include the priority policies of president-elect Prabowo Subianto. The current political transition is projected to have implications on Indonesia’s credit rating and exchange rate, subject to the filling of several key positions in Indonesia’s economic governance.

The aforementioned process brought a challenge to Indonesia’s fiscal balance. Most recently, Prabowo mentioned that his first year of administration would most likely see a 2.6-2.8% of budget deficit, which is a significant increase from the 2023 rate of 1.65%. Prabowo has also expressed his criticism towards the 3% budget deficit cap set by the current government. Thus, it is likely that Indonesia will see a brisk increase in its government expenditures.

Currently, three policies of the upcoming administration, which are supposed to be carried out on the second semester of 2024, will have immense effect to the state budget and fiscal balance.

- Free lunch programme—the controversial and populist policy is originally set to cost the state budget 450 trillion Indonesian Rupiah (≈26 billion Euro), or equivalent to 13.53% of estimate total state budget, although his team has mentioned that they’re working to press down the number. The programme, which is designed for 82,9 million school-age children, may actually cause this financial year’s state budget to reach a deficit of 3-3.2%, according to experts. The World Bank has warned Indonesia to be cautious in moving on with this policy.

- Continuity of the new Nusantara capital—Prabowo presidency brought a vision of continuity towards the development of the new Nusantara capital. Prabowo envisioned that an 440 trillion Indonesian Rupiah (≈25,5 billion Euro) budget is to be divided over several fiscal years, and that it will be contributed from various existing expenditures, such as infrastructure development.

- Defence expenditure—while there has been no further details about massive defence procurement in the upcoming fiscal year, Prabowo’s track record as Minister of Defence has alerted some parties that his administration might be seeing a ballooning defence expenditure.

Long-term overview: urgency for reform

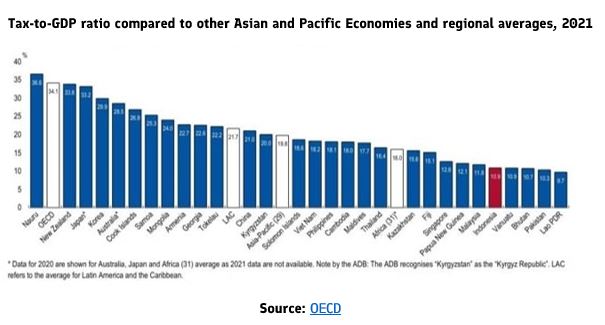

In fulfilling the upcoming government’s ambitious plans, Prabowo’s economic strategy would rely on reform towards the national revenue. Prabowo is keen to increase Indonesia’s tax-to-GDP ratio from 10% to 16-18% by increasing efficiency of tax collection system, citing references from Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Indonesia, in fact, is in the bottom five in terms of tax-to-GDP ratio in Asia-Pacific. In addition, the current average rate has been stagnant over the last decade, with the highest only being 13.0% in 2008, with an economic crisis looming in the background.

The pinnacle of Prabowo’s tax revenue reform would be the creation of a separate National Revenue Agency under the President (most likely mirroring the US model), which is derived from the Ministry of Finance’s DG of Tax. Outside of the reform in tax sector, Prabowo also vowed to decrease economic dependence towards state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and more chance towards the private sectors, citing reasons of production effectivity and a fairer market.

Regardless, Indonesia still have a long way to go in terms of economic reform. While the recent OECD decision to open accession discussion with Indonesia may be celebrated with cheers, experts reminded that the process will be full of hardships. Indonesia’s strong foundation of economic and resource nationalism is very likely to continue, with Prabowo underlining the economic policies of current President Joko Widodo (“Jokowinomics”) as the way to go. Meanwhile, OECD itself has recommended Indonesia to remove remaining private and foreign investment restrictions, implying to the down streaming and export ban policies which have been the centrepieces of Jokowinomics. The OECD has also urged Indonesia to allocate more focus towards digital and climate transitions, as well as to reform its social assistance schemes to be more effective and efficient by mainstreaming gender-specific criteria.

Domestic microeconomics and social welfare

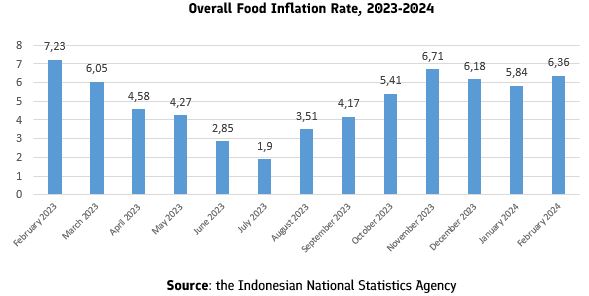

On the consumer side of the economy, the general public is struggling with the increasing price of food staples. The current administration has tried to frame the surging price as normal, citing that they are implications of the prior Ramadhan (Islamic fasting month) and Eid Fitr (major Islamic holiday), as well as the natural phenomenon El Nino. The National Statistics Agency reported that the volatile food inflation rate in February reaches 8.47%, which is the highest since last October. Meanwhile, in this year’s first quarter, the public is also seeing a rising scarcity of rice. This scarcity is set with the continued roll-out of social assistance programme by the government towards 22 million people nationwide, which took form of monthly rice packages. While the government stated that the programme is to help those impacted by the price surge, experts stated that they actually worsen the crisis. In February, the rice commodity reached an inflation rate of 5.32%.

International trade and investment

Free trade agreements (FTAs)

the negotiation on Indonesia-EU CEPA has entered its 17th round. The latest round has brought conclusion to three chapters, namely structure of the FTA, sustainable food system, and technical barrier to trade. The negotiation also almost saw the conclusion to the discussion on intellectual property rights. The current administration has shown its interest in wrapping-up the negotiation before the next administration start on October.

Other than I-EU CEPA, most prominently, Indonesia is also under negotiation for the Indonesia-Canada CEPA. Indonesia has also seen the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) coming into force since last year. While Indonesia has not felt significant positive impact on its first year (on the contrary, export to RCEP countries went down 14.04% compared to 2022), it is predicted that the RCEP will eventually bring an export increase of 5,01 billion US Dollar (≈4,7 billion Euro) by 2040.

Indonesian stakeholders are also divided over the possibility to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). While Chief Economic Affairs Minister Airlangga Hartarto mentioned that the CPTPP may be a good tool to unlock Latin American Market for Indonesian businesses, other officials doubted that such mega FTAs could mitigate the tensing global geopolitical situations.

Another important trade negotiations that Indonesia is currently engaging in is the Indonesia-Eurasian Economic Union Free Trade Agreement (IEAEU-FTA). Indonesia dubbed the union as an entryway for a new non-traditional market in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. The FTA is part of Indonesia’s aim to diversify its export segmentation.

OECD Accession

On February, the OECD made historic decision to open accession discussions with Indonesia, making it the first applicant to receive the status from Southeast Asia. The move has received praise from many parties for preventing a ‘geopolitical disaster’ by Indonesia joining the BRICS alliance. However, Indonesia still have a long, winding road to adhere to OECD’s stringent principles. Joining the OECD means Indonesia needs to amend its national and local legislation and policies to meet the OECD criteria. Some of the highlights of the needed reforms include the sectors of: (1) open trade and investment regime; (2) public governance and anti-corruption efforts; (3) environmental protection. Indonesia’s decision of moving on with OECD accession brought a sense of relief to many domestic and foreign stakeholders. This is due to the fact that a rumour of Indonesia joining BRICS was circulating in 2023, in exchange of it joining the OECD.

Palm oil and forestry

in the most recent update regarding the EU-Indonesia-Malaysia deforestation dispute in the World Trade Organization (WTO), an adjudicating panel of the international organization backs EU in the case against Malaysia. While the ruling for Malaysia has been published, it is reported that Indonesia requested a suspension to the ruling publication for two months.

Halal certification

the government of Indonesia has published a regulation that all products entering and circulating in Indonesia, with special focus on food and beverage products, must be halal certified by October 2024. The Indonesian halal certification authority, the BPJPH, opened the possibility for businesses to either gain halal certification from the Indonesian authority of the halal certification body (HCB) in their own country. The latter option, however, comes with the condition that the HCB has received accreditation from the BPJPH, which comes in the form of a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA).

This regulation might possess challenges to several EU member states, such as Finland, which does not have a national HCB. Given this challenge, the Finnish Embassy alongside with the EU Delegation in Jakarta has approached BPJPH to negotiate the terms of the recognition agreement. Among the negotiated issue are the possibility of European businesses gaining accreditation in another European countries when their home country lacks of an HCB. After previous meeting with the BPJPH, several EU member states reported that delegations from BPJPH are set to visit their countries and visit their halal certification institutes.

Written by Demas Nauvarian, Economic and Political Advisor, Embassy of Finland, Jakarta.